無相三昧4

無相三昧:指觀六塵(色、聲、香、味、觸、法)的無常。

這些表象看起來合乎佛法的字義,再來小論述。

入定-是人體對於脫胎換骨的修持,到達一個頂尖,

包括由佛法的理解產生的-入法(慧解脫)。

經過入法、入定的洗禮,人體的感官知覺會伴隨著產生變化,

這是一種人體本身歷經修持產生的大洗禮,

由於肉體的感官發生變化,對於有生命開始就有的知覺也會有不同的感受,

這種感受源自於修行的進步產生的變化,是自然而然的。

而六塵教授的色、聲、香、味、觸、法,在此時也可部分理解,

我指出是「部分理解」,因為修行者的程度不一,所以他理解佛法的程度也不一,

就像我們看到佛陀的弟子們所傳授的三昧說法也千百種,原因是;各人程度不同。

沒有上述「入法與入定」的洗禮,直接觀想六塵的無常,

試想,人體可能在生活中對色、聲、香、味時刻去鍛鍊它的無常嗎?

除非是修行者個人專精的修持,

再不然只能做佛法詞彙的理解。

我了解的很多指導都指向你可能連吃一碗飯都要計較自己的貪念頭,這實在太累與背離人性,

這種拿計算機的修法,會導致很用功的修行者,最後被扭曲並且一事無成,

不知道錯誤在哪裡也就算了,更可能還得懺悔自己的資質駑鈍,那才叫冤。

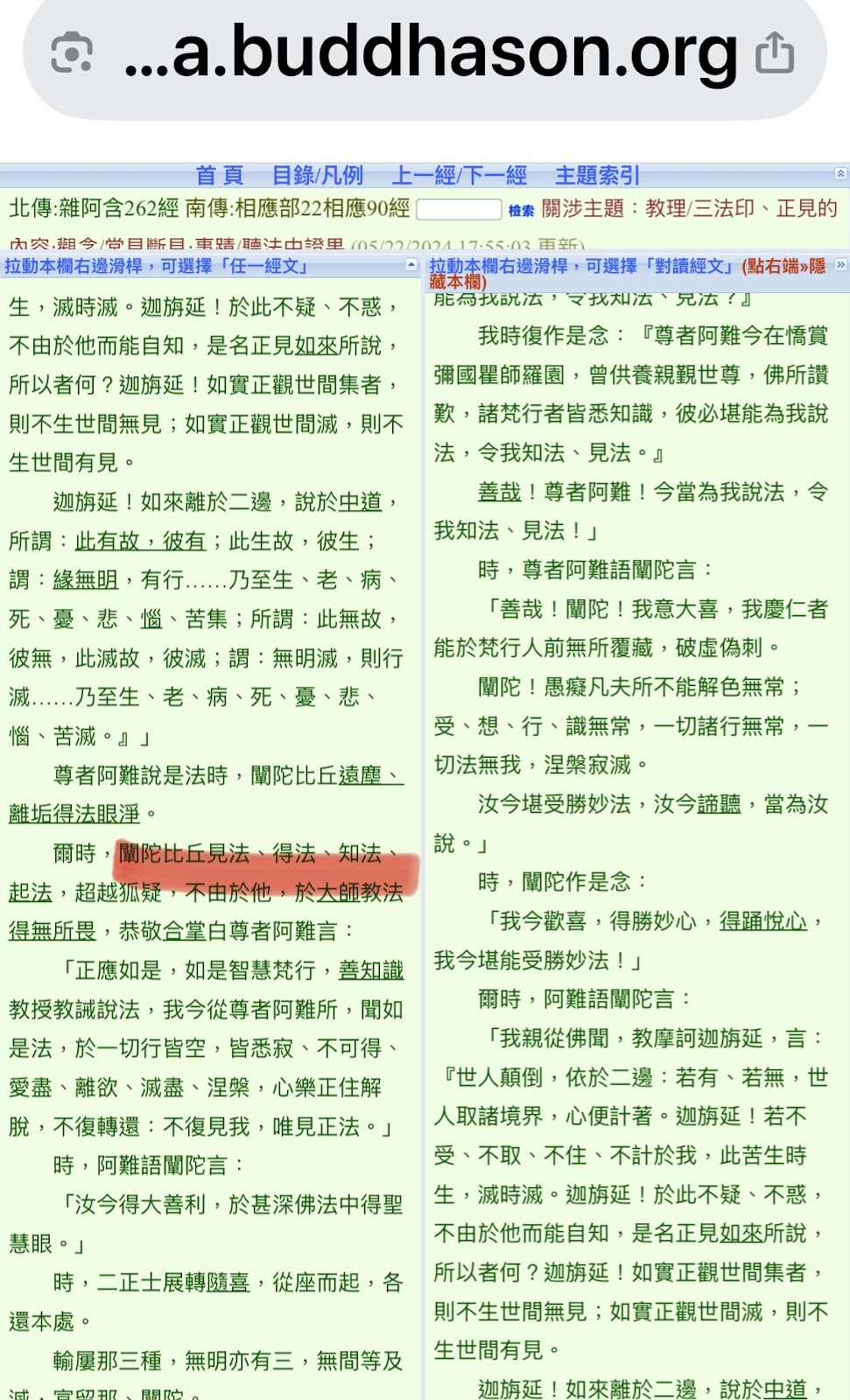

下面截圖1. 雜阿含262的經文,指出

「知法、得法、見法、起法,超越狐疑,不由於他」

(不須再從別人口中知道佛法,已經確定自己明白、清楚佛說-入法)

我個人一直很喜歡這樣的修法,

可以確切去掌握佛說,

在很繁瑣的塵事上去摸索,不如認知它的前因後果(集的提出)。

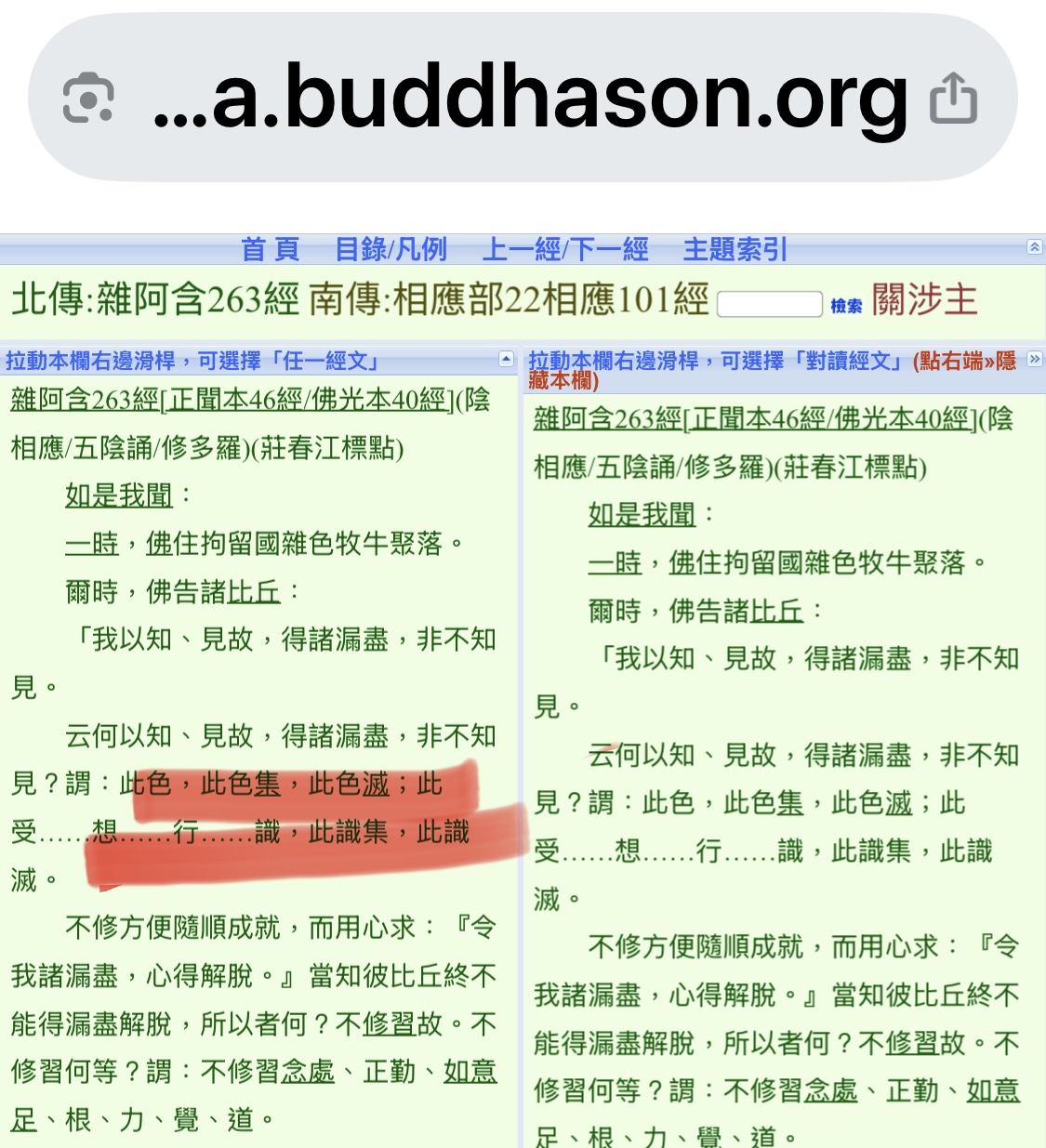

截圖2. 雜阿含263經文,

指出「此色集,色滅、識集、識滅」,依然在「因緣法」中闡述,沒提到無常。

半寄

以下AI資料 「六塵」是佛教中後期發展出來的術語,指色、聲、香、味、觸、法, 也就是六種感官對象,與「六根」(眼、耳、鼻、舌、身、意)相對應。

這一概念在阿含經(如《雜阿含經》)和後來的佛教教義中逐漸被系統化,用來描述感官與外境的互動如何引發執著與痛苦。

隨著佛教教義的發展,特別是在阿含經和部派佛教時期,六根、六塵、六識的概念逐漸被詳細闡述,用以分析認知過程和輪迴的形成。例如,《雜阿含經》中提到六根與六塵的互動,作為緣起法的一部分。 |

Formless Samādhi 4

Formless Samādhi means seeing that the six sense objects—form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mental objects—are all impermanent.

This idea fits with Buddhist teachings on the surface, and now I’ll give a short explanation.

Entering samādhi (deep meditation) means that the human body goes through a kind of transformation.

This includes understanding the Dharma deeply and entering it with wisdom—this is called entering the Dharma (wisdom-liberation).

After going through the process of entering both the Dharma and deep meditation, the body’s sense perception begins to change.

This is a powerful, natural transformation that happens after real practice.

As the body’s senses change, the way we feel and respond to the world also changes.

This new experience comes from spiritual progress, and it happens naturally.

At this stage, the six sense objects—form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mental objects—can start to be understood more deeply.

But I say "partially understood," because every practitioner is at a different level, and their understanding of the Dharma is also different.

That’s why the Buddha’s disciples explained different kinds of samādhi—there are many, depending on each person’s ability.

If someone hasn’t gone through the deep process of entering the Dharma and entering samādhi,

it’s hard to just “meditate on the impermanence” of the six sense objects.

Can a person really train their mind to see impermanence in form, sound, smell, and taste while doing daily tasks?

Only if they’re a serious practitioner. Otherwise, it’s just a matter of understanding words in the Buddhist texts.

Some teachings even suggest that you should watch your mind while eating, and keep track of how greedy you are.

But to me, that’s exhausting and goes against human nature.

This kind of "calculator-style" practice makes people overly tense. Even if they work hard, they may achieve nothing in the end,

not even knowing where they went wrong. And worse, they might blame themselves for being “dull,” which is a real pity.

Below is Screenshot 1: a verse from Saṃyukta Āgama 262 says:

“Knowing the Dharma, attaining the Dharma, seeing the Dharma, giving rise to the Dharma—beyond doubt, not relying on others.”

(This means you no longer need others to explain it; you know for yourself what the Buddha taught. That’s entering the Dharma.)

I personally love this kind of practice.

It allows you to clearly understand what the Buddha meant.

Rather than struggling in worldly matters, it’s better to understand the cause and effect behind them (the teaching of origin).

Screenshot 2: from Saṃyukta Āgama 263,

It says “the arising and cessation of form and consciousness,” and explains this through dependent origination, but doesn’t talk about impermanence directly.

Master Banji

AI Data: The “six sense objects” (ṣaḍviṣaya) are a term developed in later Buddhism. They refer to form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mental objects—what our six senses perceive. These match the “six sense bases”: eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind.

This concept was gradually developed and systematized in early texts like the Saṃyukta Āgama, and later Buddhist teachings. It explains how the interaction between senses and the outside world causes attachment and suffering. In early Buddhism and Abhidharma systems, the ideas of the six sense bases, six sense objects, and six kinds of consciousness were deeply explored to explain perception and how rebirth works. |

|

「六塵」是佛教中後期發展出來的術語, 指色、聲、香、味、觸、法 也就是六種感官對象,與「六根」 (眼、耳、鼻、舌、身、意)相對 這一概念在阿含經(如《雜阿含經》) 和後來的佛教教義中逐漸被系 用來描述感官與外境的互動如何引發執著與痛苦。 隨著佛教教義的發展, 特別是在阿含經和部派佛教時期, 六根、六塵 用以分析認知過程和輪迴的形成。 《雜阿含經》中提到六根與六塵的互動, |